Challenges and Risks of Jesuit University Networks

Author: Susana Di Trolio - Executive Secretary of the Kircher Network

In the previous article, “A View on Jesuit University Networks”, we took a look at the context in which Jesuit university networks have developed in recent decades. We also asked about the usefulness of such networks and the circumstances in which their creation is desirable, and presented some answers.

In this second post, we will review the main challenges and risks of Jesuit university networks. To do so, I have summarised and grouped these challenges and risks into five broad categories.

Graphic in Spanish (original language of this post)

Defining clear and achievable objectives and results: the iron law of contexts

The contexts in which the 189 Jesuit universities operate in more than 50 countries are highly complex and differ markedly from one another. Depending on their capacities and strengths, each institution seeks to fulfil its apostolic mission and the inescapable and complex demands of quality in formation and research in increasingly competitive and changing contexts. At the same time, to fulfil its mission, the Jesuit university has to be economically sustainable. Maintaining a balance between these three dimensions is the main task of the university authorities.

Networks exist to support and serve universities. Hence, the first major challenge for networks is to understand the differences that exist among Jesuit universities, especially in their capacities, strategic lines, organisation and governance structure, as well as in the regulations and characteristics of the respective higher education markets.

Given this diversity of Jesuit universities, networks must be able to identify common projects and initiatives that are viable and with clear and concrete objectives that add value and involve the greatest number of institutions. The common project or initiative is the node of networking. Those of us who collaborate in the formulation of international inter-university projects know that this is a complex task that requires listening, leadership and negotiation.

Networks can fail to define objectives and outcomes. When this happens, the network loses momentum, becomes paralysed and eventually disperses. In the next article we will look at some of the factors that help explain the success or failure of networks in this key task of goal setting.

Availability of resources and capabilities: The iron law of limited resources

The second challenge that Jesuit university networks must overcome is that of being able to function and develop projects and initiatives with the human and financial resources available. That is, defining an efficient and sustainable funding model for the network. Although there are differences between universities or between regions in the resources and possibilities of access to funding, these are generally limited.

Some of you might disagree with this statement and think that, being a global organisation, the Society of Jesus and its universities should have enormous financial capacity and leverage. This is not the place to reflect on that issue. In the last post we will look at the lessons learned in terms of network funding models and the search for funding.

But we can say that university networks must be able to plan projects with achievable and sustainable objectives, goals and results with the resources and capacities at their disposal. It is of little use to define an ambitious project, but with oversized goals: how many great inter-university projects have we seen that are not implemented and network members exhausted and disappointed by what they might consider a lack of support? Therefore, the coupling of ends, means and timelines of projects or initiatives is key.

Political will and leadership: The commitment to collaborative networking

Jesuit university networks are made up of the institutions, the academics and professionals who develop collaborative work, and the central teams of the presidency and executive secretariats. All three actors require support, capacity and leadership, especially in the Ignatian style. For reasons of time, in this article I will only refer to the role of the institutions. In the third section of Table 1 you will see the importance of network coordination.

For the network to function, the political will of the member universities and institutions is required. In particular, the support of the rectors for the network and the collaborative work it develops is indispensable. This political will of the authorities in favour of the network is particularly important in the start-up phase of networks, where they have not achieved the legitimacy that comes from the successful implementation of value-adding initiatives. Some of you may argue that authorities cannot force academics and civil servants to participate in any network, even if it is a Jesuit one. This is true. However, it is also true that no member of universities will participate in a Jesuit network if he or she does not see the clear interest of the authorities in such work or, in the worst case, if the message is that the network or its projects are not viable or not in the interest of the institution. The risk for the network is to have a deficit of strategic stakeholders. The challenge for the network, especially in its early days, is to get out of the “chicken and egg” trap; there is no political will and therefore the availability of academics and practitioners is scarce, which in turn limits the development of projects and the legitimacy of the network. We will have to wait for the next post to see some lessons learned.

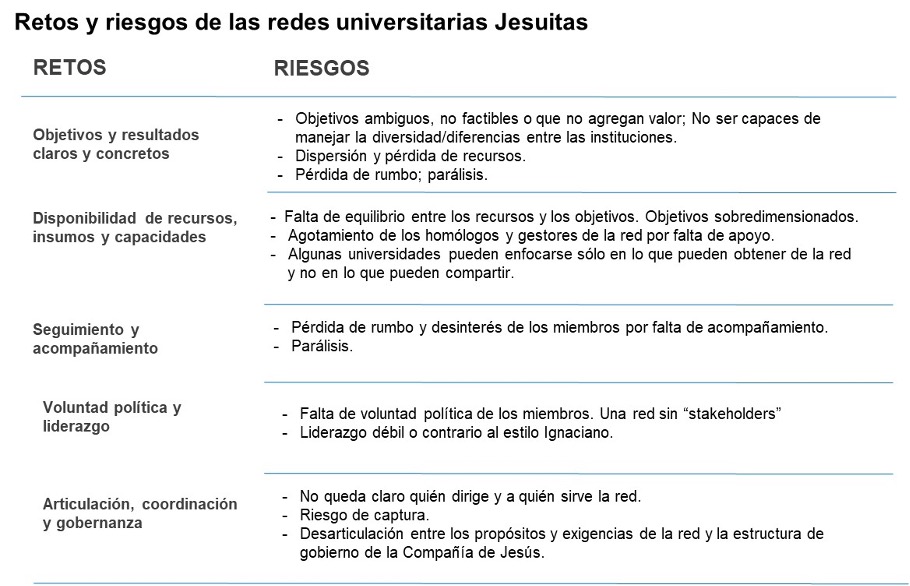

Articulation, coordination and governance of networks: The challenge of strengthening the universal body for the same mission

As mentioned in the previous article, the last two decades have witnessed a steady growth in the creation of Jesuit university networks, as well as a strengthening and transformation of existing ones. This process of creation and transformation is not yet complete. In Table 2, we present a map of the six regional networks and the three disciplinary and global networks coordinated under the umbrella of the IAJU (International Association of Jesuit Universities).

The challenge for the networks and for the governance of the Society of Jesus is to clearly define the articulation of the networks with the member institutions, with the governance structure of the Society of Jesus and with other local and international Jesuit networks. In each case, it is necessary to define whom the network serves and with whom it collaborates (e.g. the province, the regional conference of provincials, the universities, the Secretariat for Higher Education of the Society of Jesus). It should also be clear who leads and how the network’s leaders are chosen and to whom they are accountable.

But beyond the governance structure, there is the challenge of ensuring coordination and collaboration, including funding, between the university networks and the provinces, conferences and other Jesuit apostolic networks. There is also a need to foster collaboration with other non-Jesuit organisations. We know that this articulation is not easy and that it requires openness and putting into practice our sense of seeing ourselves as collaborators for the same mission. It is legitimate to think that this is a nice phrase. So, for the sceptics, I ask you: given the magnitude of the mission and the existence of limited resources, does it make any sense or usefulness to be trapped and blinded by the organisational boundaries of works, provinces and networks? Do we think that, for the greater good, Our Lord cares about organisational boundaries and the small fruits of each organisation?

In the next and last post, some of the lessons learned and good practices for the creation and good functioning of Jesuit university networks.